José Vera Matos

Bio/CV

Available works

José Vera Matos

José Vera Matos

José Vera Matos (1981) lives and works in Lima, Perú. His recent exhibitions include: MALI-Museo de Arte de Lima (solo show); The Milan Triennial, Italy; Fondation Cartier pour l’art Contemporain, Paris; Sala Alcalá, Madrid; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen; Delfina Foundation, London; Museo del Barrio, New York; MALI – Museo de Arte de Lima, Peru; Nordenhake Gallery, among others. Vera Matos’ work can be found in collections such as: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid; Thyssen Bornemisza, Madrid; Fondation Cartier pour l’art Contemporain, Paris, France; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Copenhage, Dinamarca; MALI – Museo de Arte de Lima.

He was recently selected to be a part of Phaidon’s Vitamin D3: Today’s Best in Contemporary Drawing.

He was recently selected to be a part of Phaidon’s Vitamin D3: Today’s Best in Contemporary Drawing.

Bio/CV

José Vera Matos

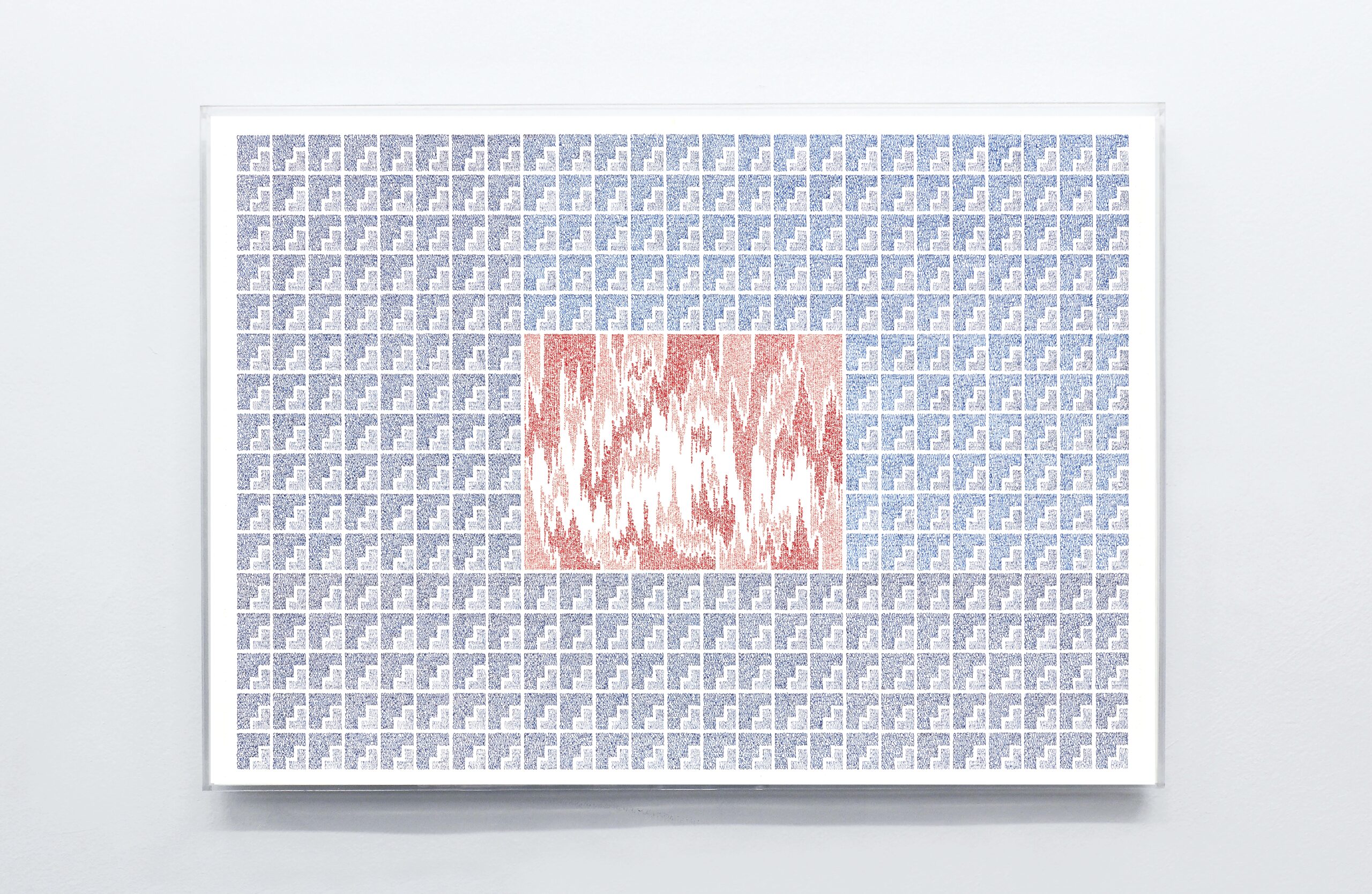

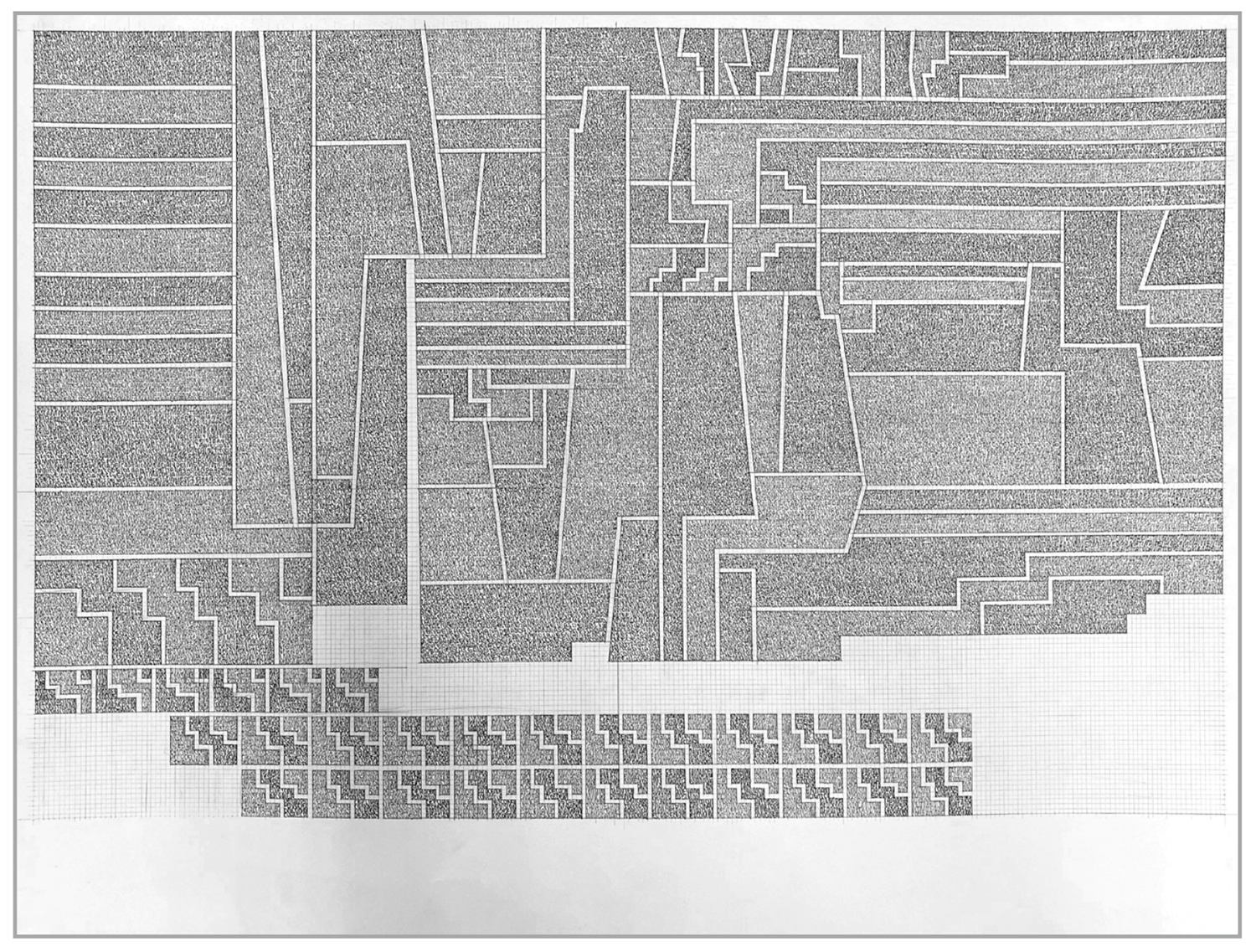

José Vera Matos’ drawings and transcriptions reflect on language and writing as essential tools for the conquest and domination of the Americas, but also on how those same tools later became a means of resistance used throughout history. The selected texts deal with a variety of aspects of the impact that the conquest had on the Americas. More than the historical event in and of itself what interests Vera Matos are the consequences and phenomena resulting from that violent clash between the two cultures. Colonial violence and resistance movements throughout history make themselves felt not only in wars of conquest and anti-colonial struggles, but also—later—in a number of facets of daily life beset by the tension between the “civilized” and the “savage,” between official culture and popular culture, between the Western and the indigenous. To translate the content of the transcribed texts into an image, Vera Matos uses columns of text that make direct reference to the Spanish language and to language more broadly as an instrument of domination and control. The use of geometric elements and patterns present throughout pre-Columbian iconography visually affect those columns. Just as those columns of vertical text represent the forced imposition of a new way of thinking, the use of tiered and trapezoidal pre-Columbian patterns found in Incan tocapus and architecture, Tiwanaku pottery, and Paracas textiles serve to manifest rejection of and opposition to things Spanish.

The use of pre-Hispanic geometric patterns and simple geometries is also a reference to the introduction in Latin America of European modernist ideas in the thirties, particularly in the work of Joaquín Torres García. He envisioned pre-Hispanic art as a symbolic representation of the conceptual evidenced through geometry. It is also an approach to the construction of a new iconography conceived and designed by indigenist thinking that emerged in that same decade in order to build an identity wholly free of European ideas and culture. Thus, indigenous cultures are revalidated and mechanisms of racial discrimination that date back to colonial times questioned. Torres García himself pursued a midpoint between the two cultural extremes.

Words are, ultimately, what visually compose the setting in which the information in the books rewritten ceases to be linear and the order of reading is altered to become random; the text is hidden and distributed between rectangular blocks and geometric elements which convey the tensions and ruptures, as well as the alignments, between two totally different ways of understanding reality.

The use of pre-Hispanic geometric patterns and simple geometries is also a reference to the introduction in Latin America of European modernist ideas in the thirties, particularly in the work of Joaquín Torres García. He envisioned pre-Hispanic art as a symbolic representation of the conceptual evidenced through geometry. It is also an approach to the construction of a new iconography conceived and designed by indigenist thinking that emerged in that same decade in order to build an identity wholly free of European ideas and culture. Thus, indigenous cultures are revalidated and mechanisms of racial discrimination that date back to colonial times questioned. Torres García himself pursued a midpoint between the two cultural extremes.

Words are, ultimately, what visually compose the setting in which the information in the books rewritten ceases to be linear and the order of reading is altered to become random; the text is hidden and distributed between rectangular blocks and geometric elements which convey the tensions and ruptures, as well as the alignments, between two totally different ways of understanding reality.

Available works

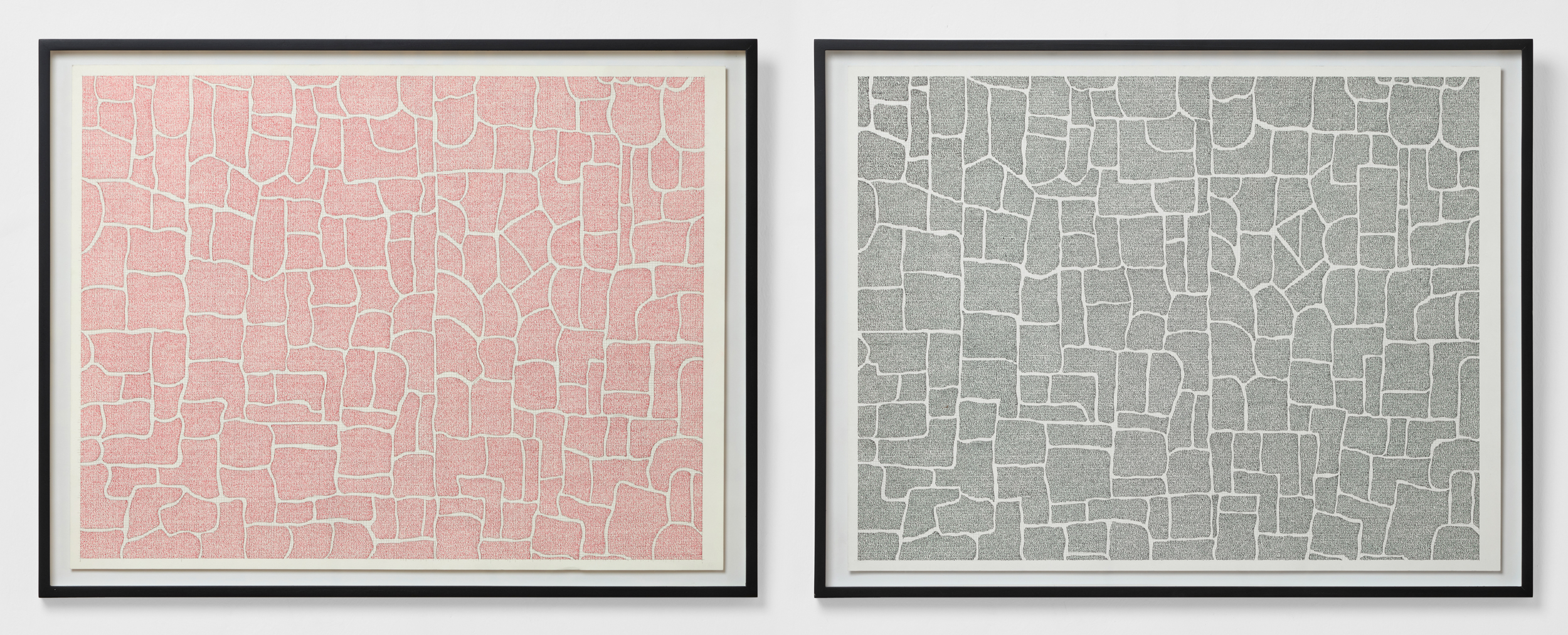

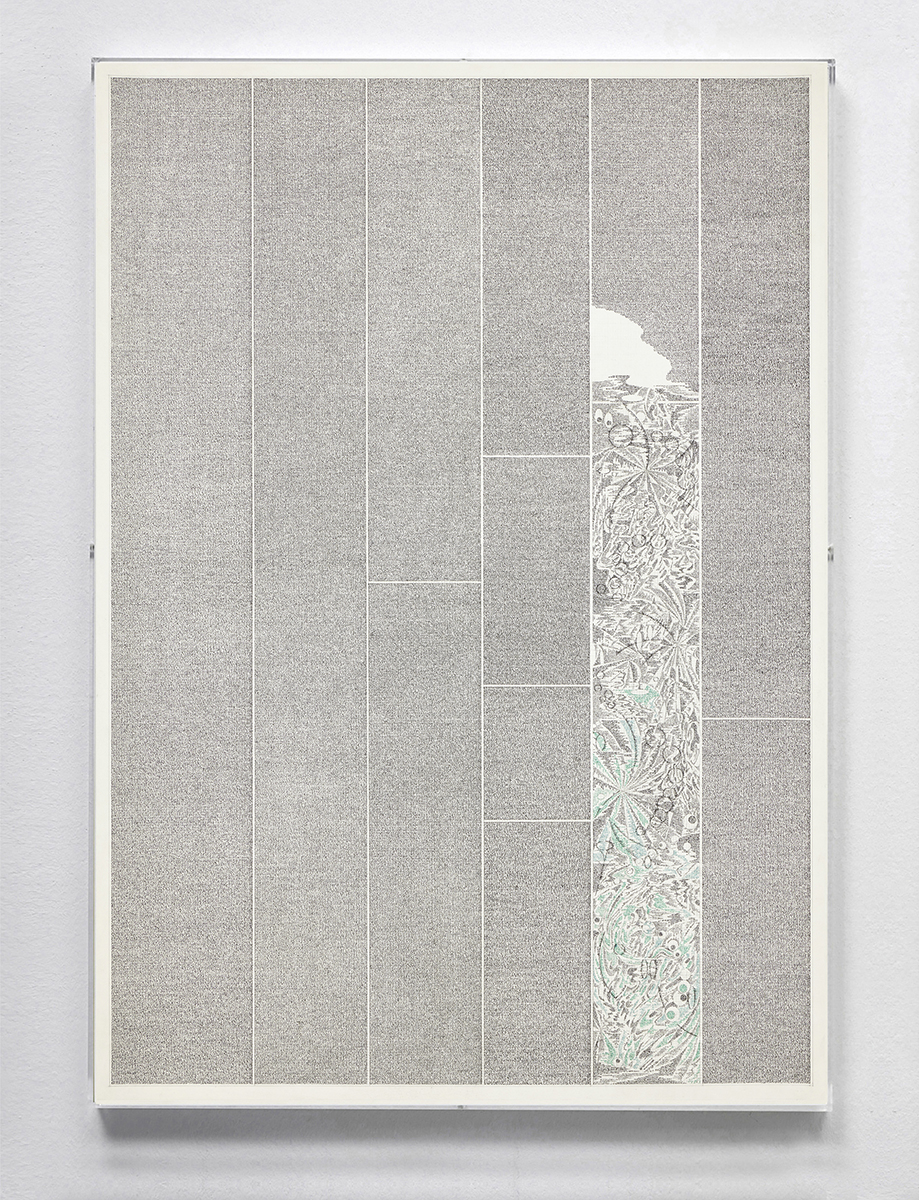

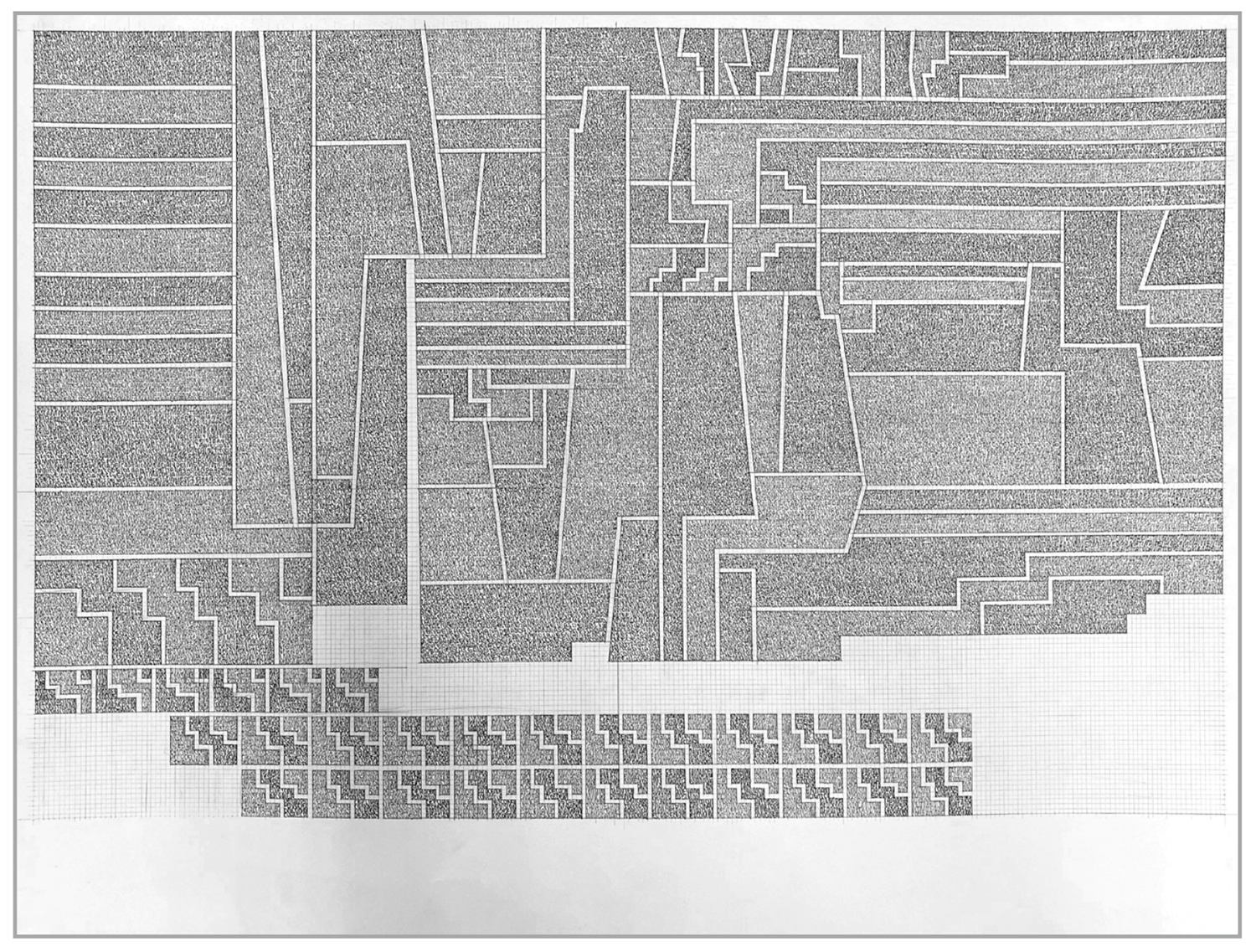

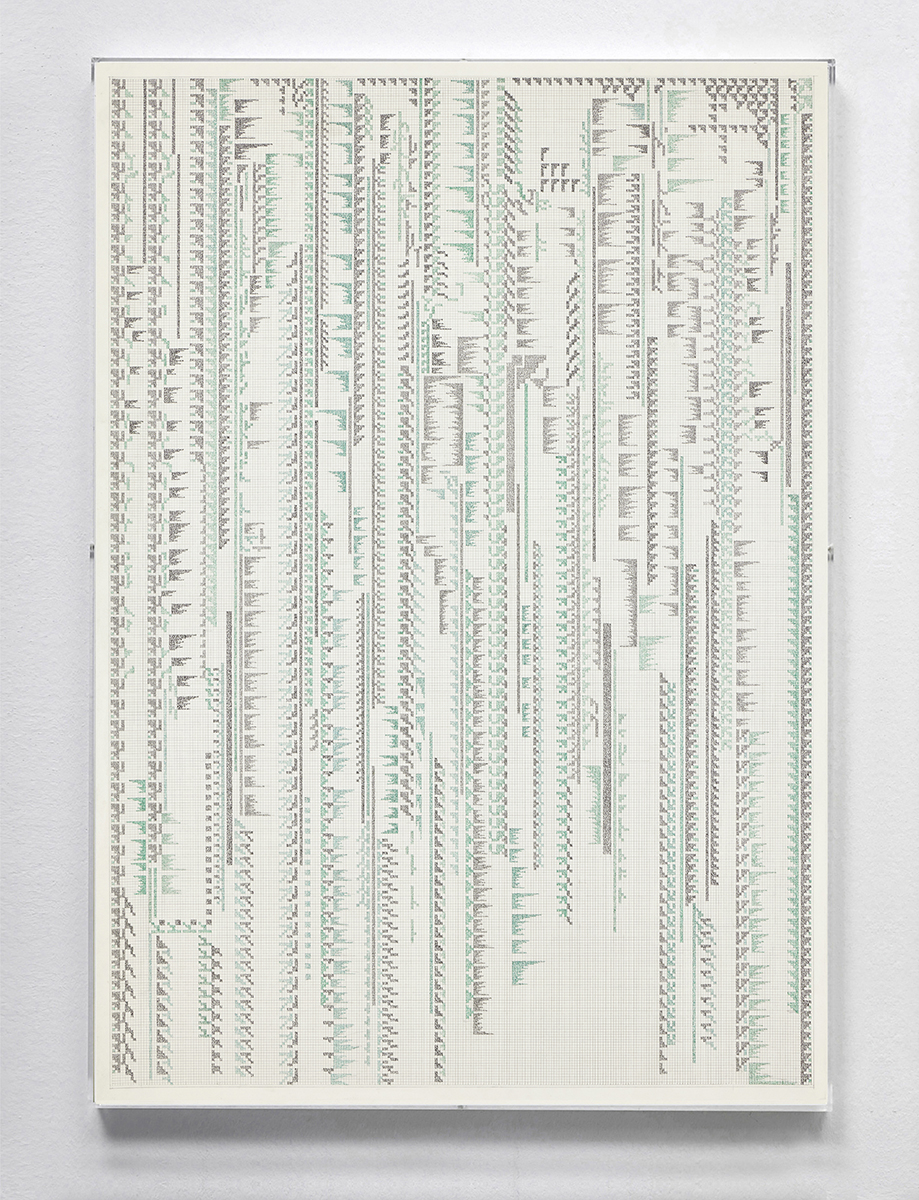

Díptico: Transcripción a mano del capítulo «Rizoma» del libro Mil Mesetas, de Deleuze y Guattari, 2025

84 x 105 cm (c/u)

Ink on paper

Tríptico: Transcripción manuscrita del capítulo «Rizoma» del libro Mil mesetas, de Deleuze y Guattari, 2025

50 x 65 cm (c/u)

Ink on paper

Handwritten transcription of Revista Amauta “AMAUTA 23 (I)”, 2024

50 x 65 cm

Stylograph and graphite on bamboo paper

“Mil Lenguas Propias I” handwritten transcription of the book “Autobiography of an Octopus” by Vinciane Despret”, 2024

100 x 70 cm

Ink on paper

“Mil Lenguas Propias II” handwritten transcription of the book “Autobiography of an Octopus” by Vinciane Despret”, 2024

100 x 70 cm

Ink on paper

“Mil Lenguas Propias III” handwritten transcription of the book “Autobiography of an Octopus” by Vinciane Despret”, 2024

100 x 70 cm

Ink on paper

“Mil Lenguas Propias IV” handwritten transcription of the book “Autobiography of an Octopus” by Vinciane Despret”, 2024

100 x 70 cm

Ink on paper

“Mil Lenguas Propias V” handwritten transcription of the book “Autobiography of an Octopus” by Vinciane Despret”, 2024

100 x 70 cm

Ink on paper

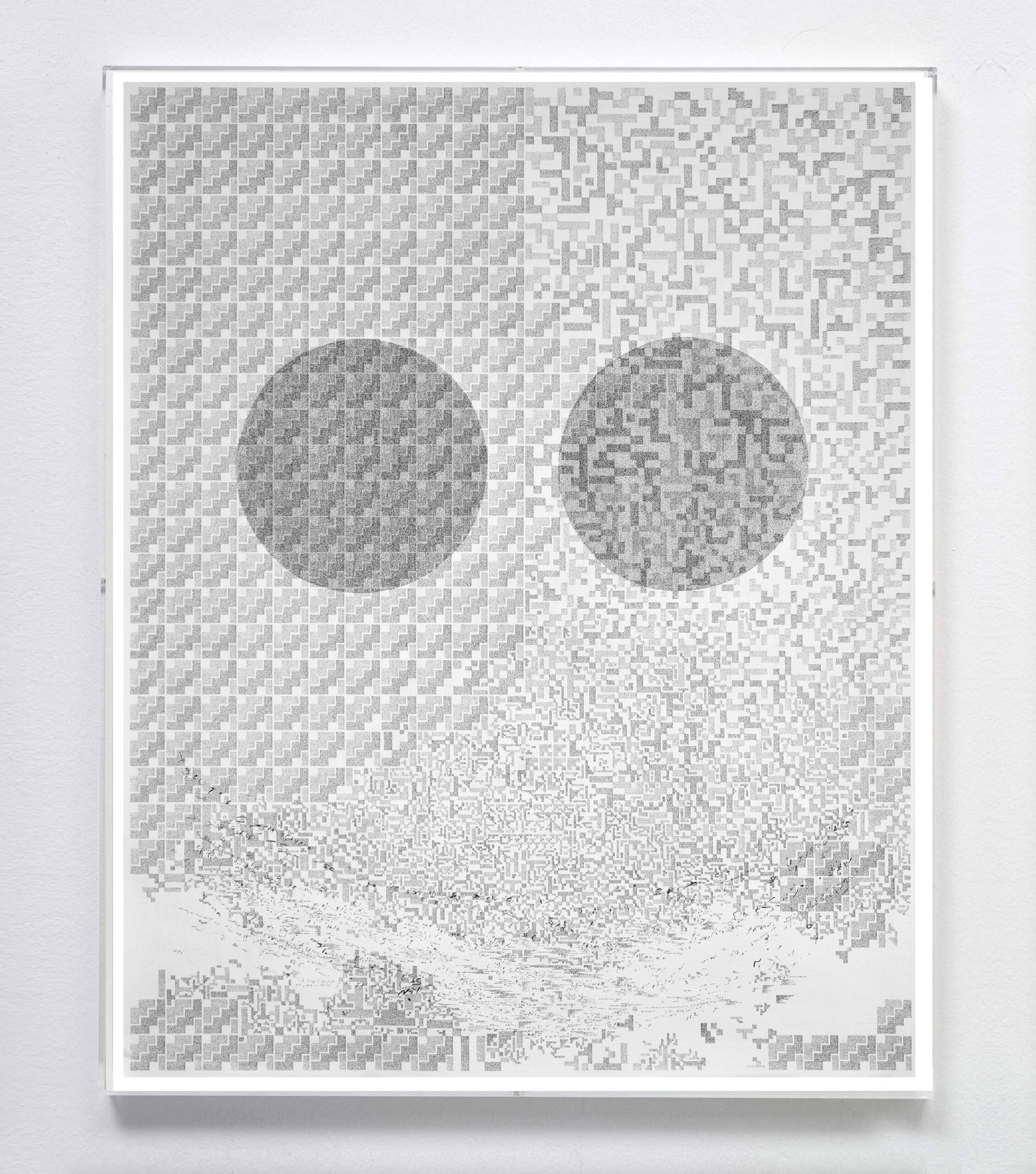

“Un libro sonríe / Una canción se Burla” Transcripción a mano del Libro “Tempestad en Los Andes” de Luis. E Valcárcel y fragmentos de la canción “Las Colinas” de V.A Gil Mallma / “Picaflor de Los Andes”, 2023

125 x 100 cm

Ink on cotton paper

Hand transcription of Edouard Glissant’s book “Poetics of Relation”, 2023

65 x 50 cm

Ink and graphite on bamboo paper

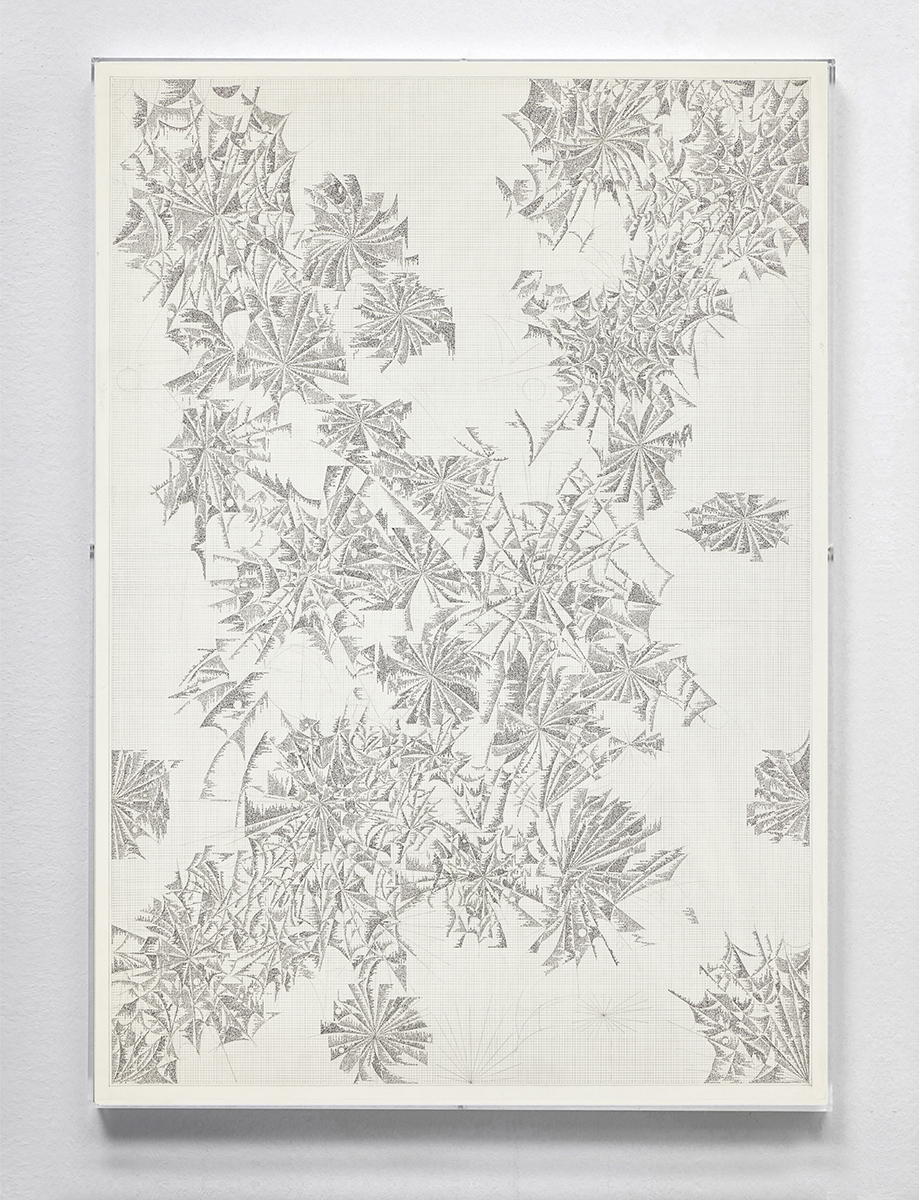

Handwritten transcription of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s book “A thousand Plateaus”, 2022

65 x 50 cm

Stylographs on cotton paper

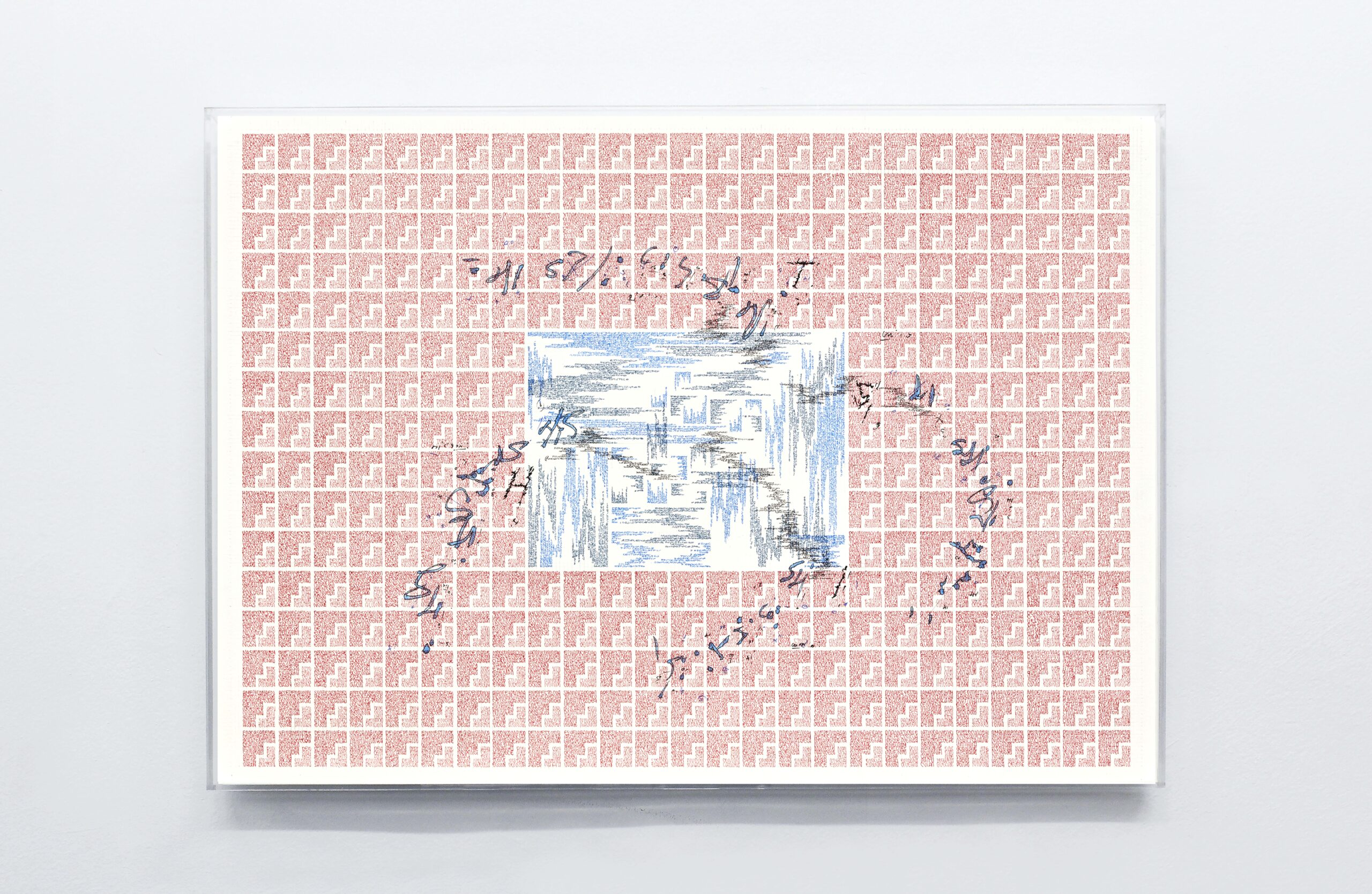

Handwritten transcription of Edouard Glissant’s book “Poetics of Relation”, 2021

42 x 60 cm

Stylographs on cotton paper

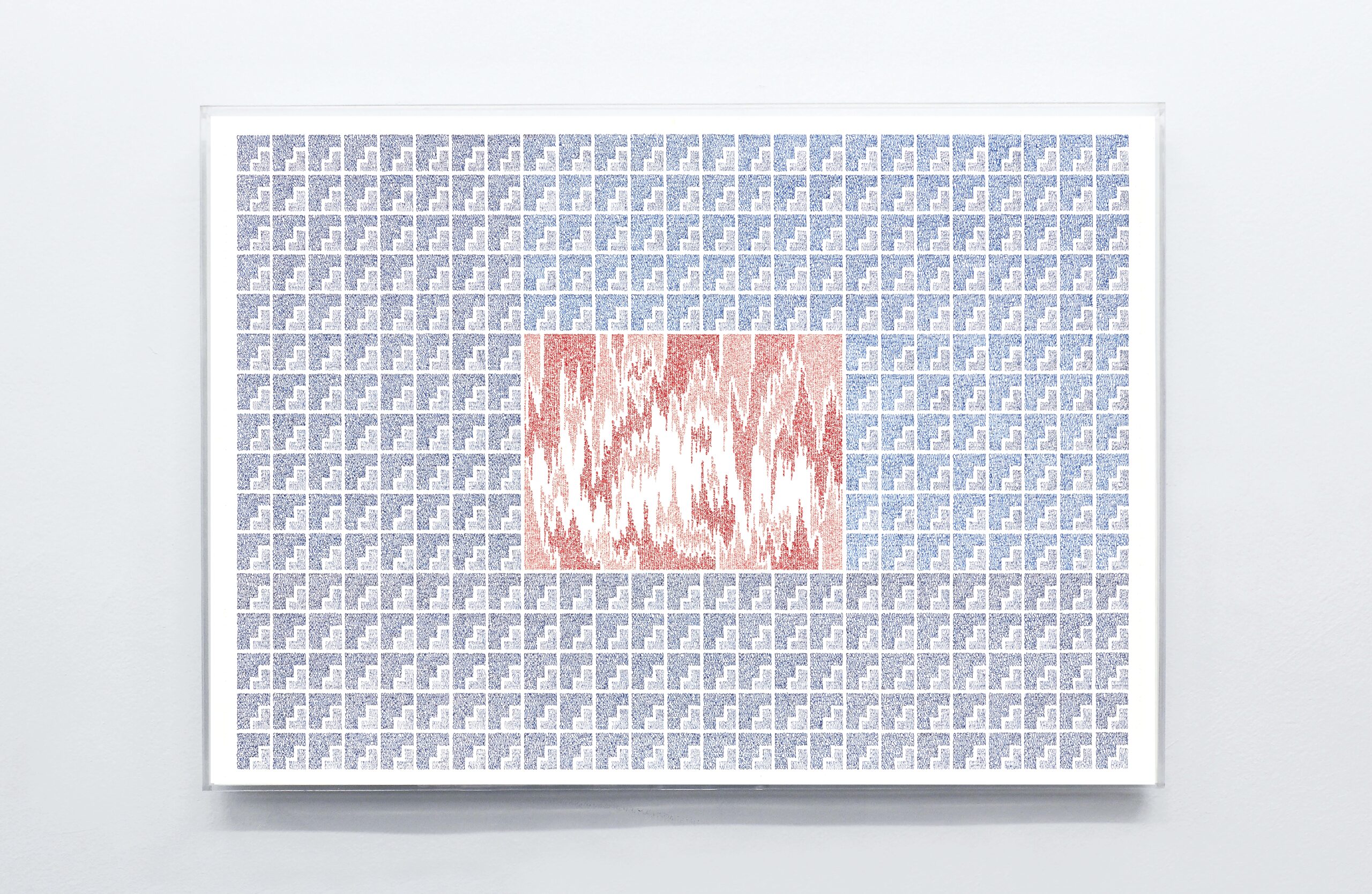

Handwritten transcription of Edouard Glissant’s book “Poetics of Relation”, 2021

42 x 60 cm

Stylographs on cotton paper

José Vera Matos

José Vera Matos (1981) lives and works in Lima, Perú. His recent exhibitions include: MALI-Museo de Arte de Lima (solo show); The Milan Triennial, Italy; Fondation Cartier pour l’art Contemporain, Paris; Sala Alcalá, Madrid; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen; Delfina Foundation, London; Museo del Barrio, New York; MALI – Museo de Arte de Lima, Peru; Nordenhake Gallery, among others. Vera Matos’ work can be found in collections such as: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid; Thyssen Bornemisza, Madrid; Fondation Cartier pour l’art Contemporain, Paris, France; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Copenhage, Dinamarca; MALI – Museo de Arte de Lima.

He was recently selected to be a part of Phaidon’s Vitamin D3: Today’s Best in Contemporary Drawing.

He was recently selected to be a part of Phaidon’s Vitamin D3: Today’s Best in Contemporary Drawing.

José Vera Matos

José Vera Matos’ drawings and transcriptions reflect on language and writing as essential tools for the conquest and domination of the Americas, but also on how those same tools later became a means of resistance used throughout history. The selected texts deal with a variety of aspects of the impact that the conquest had on the Americas. More than the historical event in and of itself what interests Vera Matos are the consequences and phenomena resulting from that violent clash between the two cultures. Colonial violence and resistance movements throughout history make themselves felt not only in wars of conquest and anti-colonial struggles, but also—later—in a number of facets of daily life beset by the tension between the “civilized” and the “savage,” between official culture and popular culture, between the Western and the indigenous. To translate the content of the transcribed texts into an image, Vera Matos uses columns of text that make direct reference to the Spanish language and to language more broadly as an instrument of domination and control. The use of geometric elements and patterns present throughout pre-Columbian iconography visually affect those columns. Just as those columns of vertical text represent the forced imposition of a new way of thinking, the use of tiered and trapezoidal pre-Columbian patterns found in Incan tocapus and architecture, Tiwanaku pottery, and Paracas textiles serve to manifest rejection of and opposition to things Spanish.

The use of pre-Hispanic geometric patterns and simple geometries is also a reference to the introduction in Latin America of European modernist ideas in the thirties, particularly in the work of Joaquín Torres García. He envisioned pre-Hispanic art as a symbolic representation of the conceptual evidenced through geometry. It is also an approach to the construction of a new iconography conceived and designed by indigenist thinking that emerged in that same decade in order to build an identity wholly free of European ideas and culture. Thus, indigenous cultures are revalidated and mechanisms of racial discrimination that date back to colonial times questioned. Torres García himself pursued a midpoint between the two cultural extremes.

Words are, ultimately, what visually compose the setting in which the information in the books rewritten ceases to be linear and the order of reading is altered to become random; the text is hidden and distributed between rectangular blocks and geometric elements which convey the tensions and ruptures, as well as the alignments, between two totally different ways of understanding reality.

The use of pre-Hispanic geometric patterns and simple geometries is also a reference to the introduction in Latin America of European modernist ideas in the thirties, particularly in the work of Joaquín Torres García. He envisioned pre-Hispanic art as a symbolic representation of the conceptual evidenced through geometry. It is also an approach to the construction of a new iconography conceived and designed by indigenist thinking that emerged in that same decade in order to build an identity wholly free of European ideas and culture. Thus, indigenous cultures are revalidated and mechanisms of racial discrimination that date back to colonial times questioned. Torres García himself pursued a midpoint between the two cultural extremes.

Words are, ultimately, what visually compose the setting in which the information in the books rewritten ceases to be linear and the order of reading is altered to become random; the text is hidden and distributed between rectangular blocks and geometric elements which convey the tensions and ruptures, as well as the alignments, between two totally different ways of understanding reality.

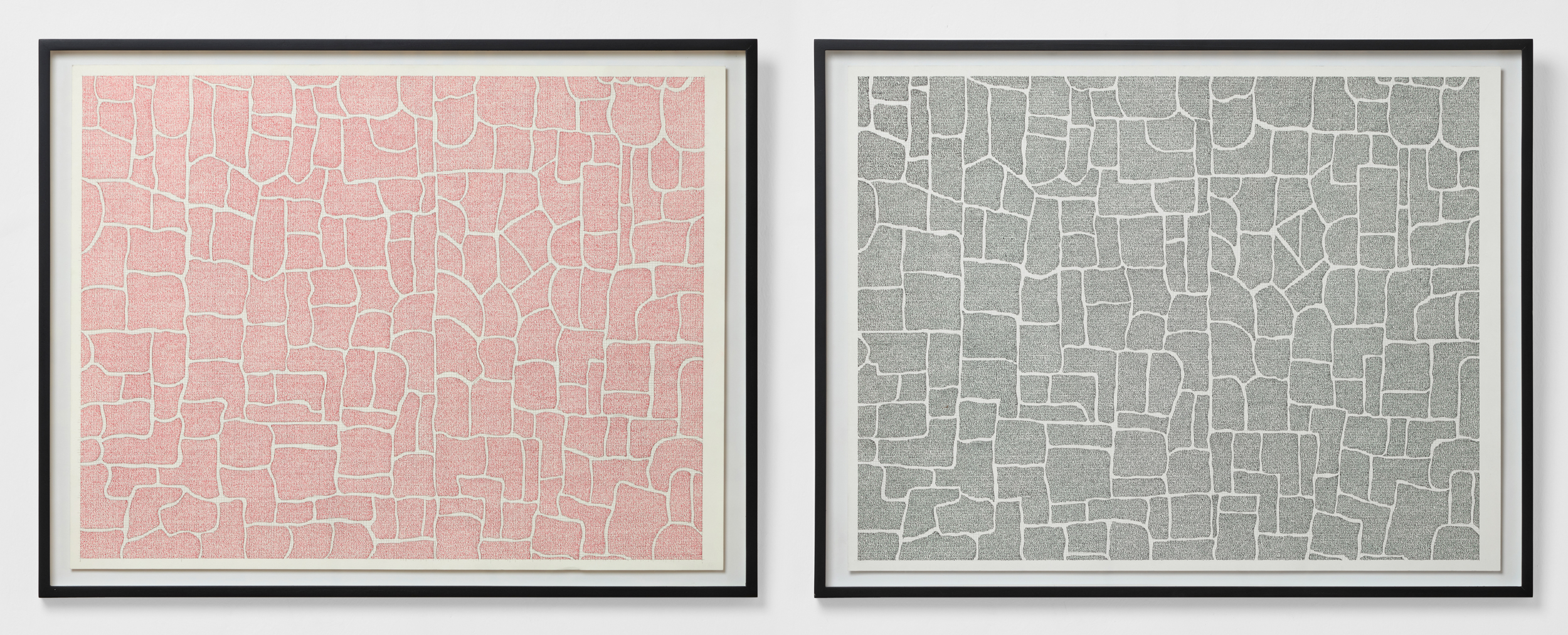

Díptico: Transcripción a mano del capítulo «Rizoma» del libro Mil Mesetas, de Deleuze y Guattari, 2025

84 x 105 cm (c/u)

Ink on paper

Tríptico: Transcripción manuscrita del capítulo «Rizoma» del libro Mil mesetas, de Deleuze y Guattari, 2025

50 x 65 cm (c/u)

Ink on paper

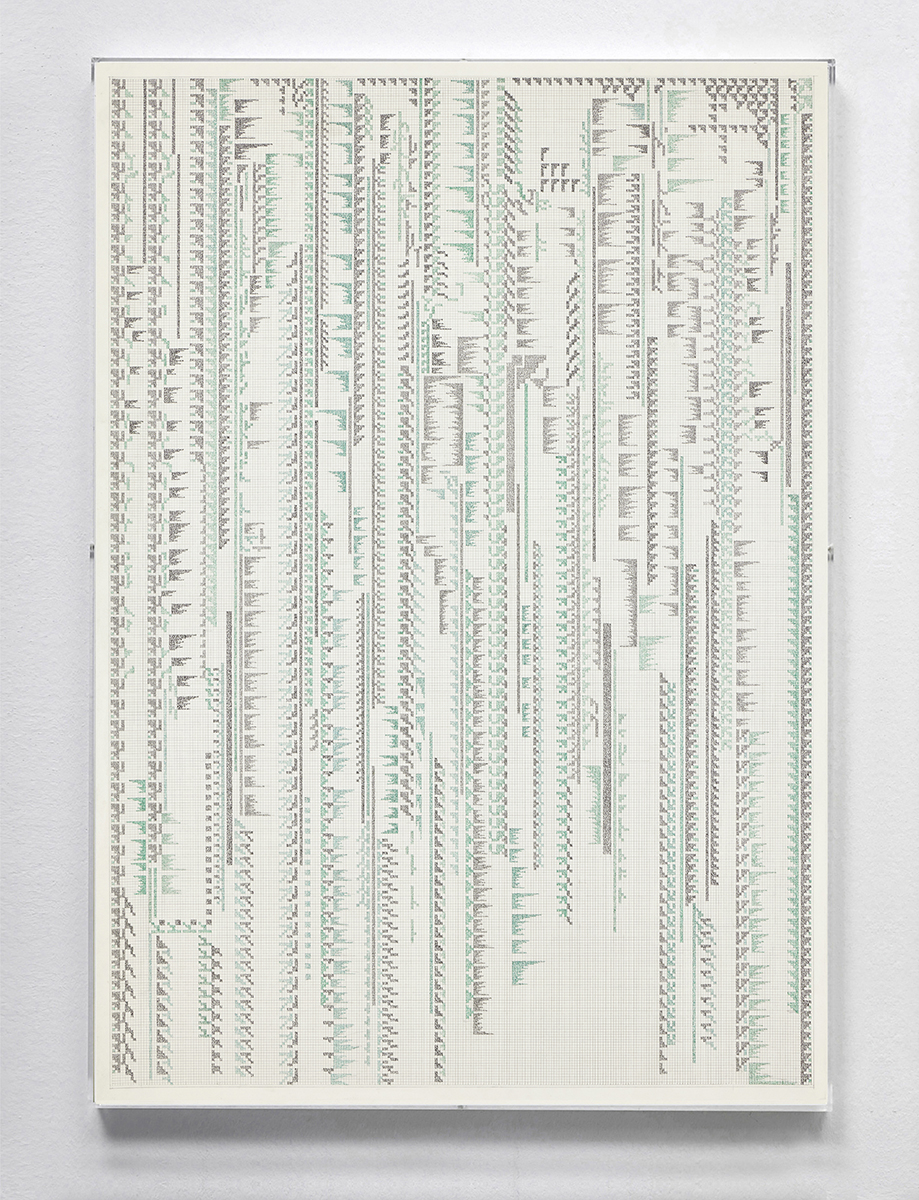

Handwritten transcription of Revista Amauta “AMAUTA 23 (I)”, 2024

50 x 65 cm

Stylograph and graphite on bamboo paper

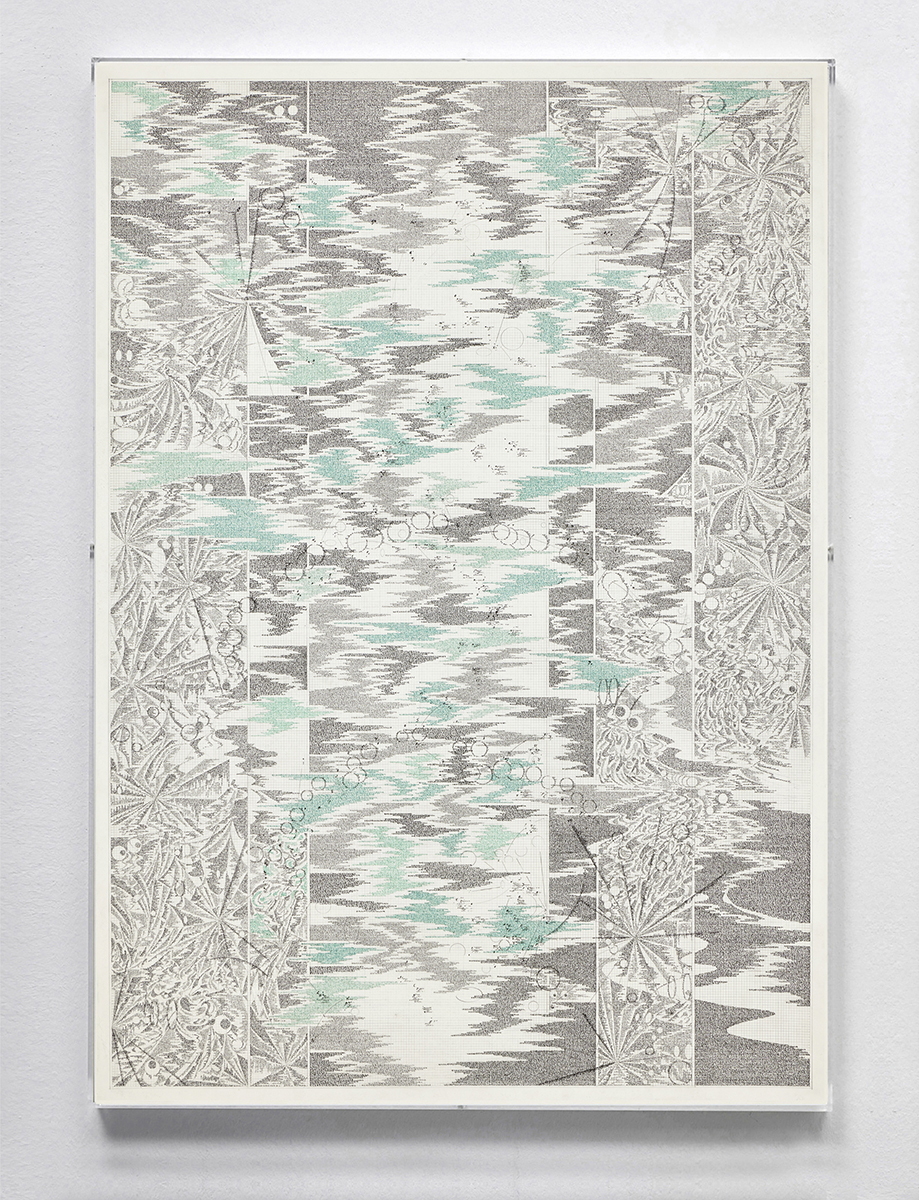

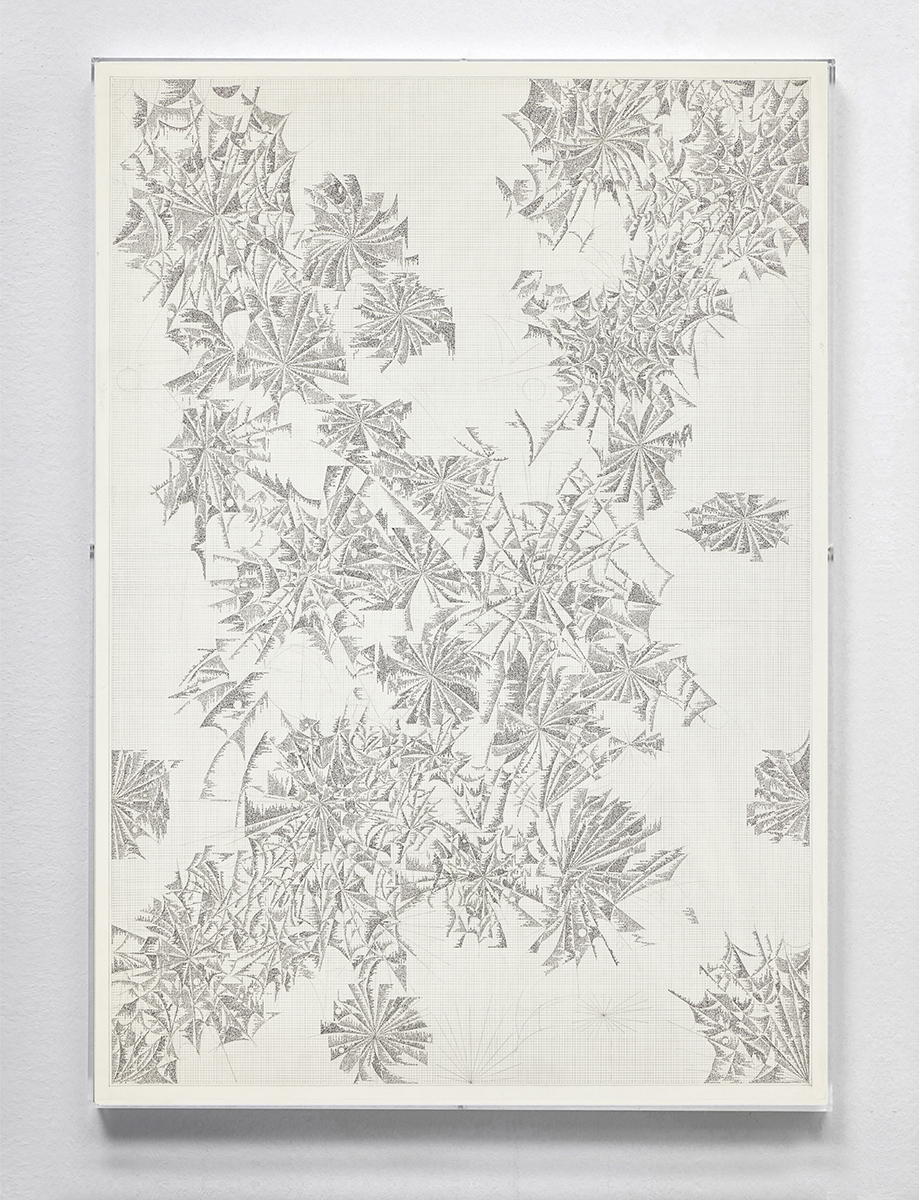

“Mil Lenguas Propias I” handwritten transcription of the book “Autobiography of an Octopus” by Vinciane Despret”, 2024

100 x 70 cm

Ink on paper

“Mil Lenguas Propias II” handwritten transcription of the book “Autobiography of an Octopus” by Vinciane Despret”, 2024

100 x 70 cm

Ink on paper

“Mil Lenguas Propias III” handwritten transcription of the book “Autobiography of an Octopus” by Vinciane Despret”, 2024

100 x 70 cm

Ink on paper

“Mil Lenguas Propias IV” handwritten transcription of the book “Autobiography of an Octopus” by Vinciane Despret”, 2024

100 x 70 cm

Ink on paper

“Mil Lenguas Propias V” handwritten transcription of the book “Autobiography of an Octopus” by Vinciane Despret”, 2024

100 x 70 cm

Ink on paper

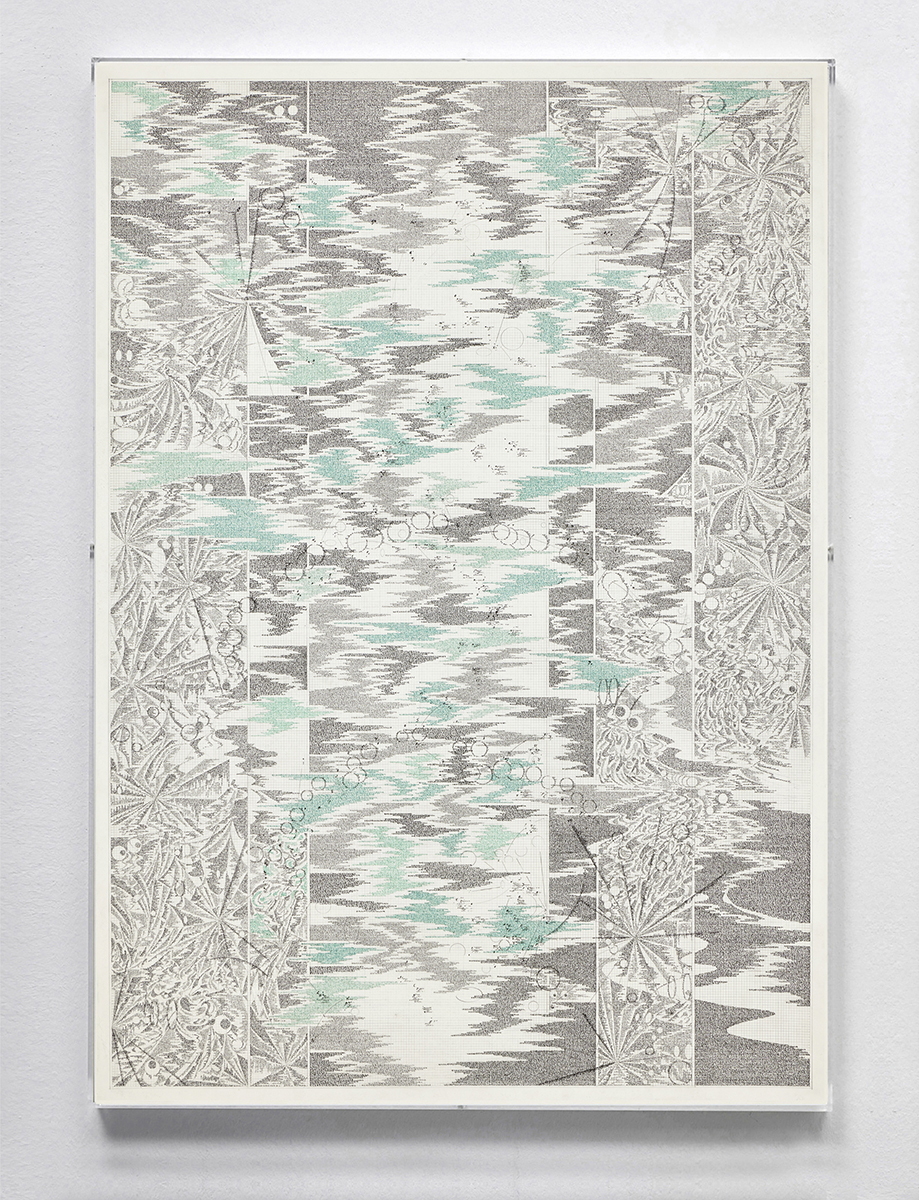

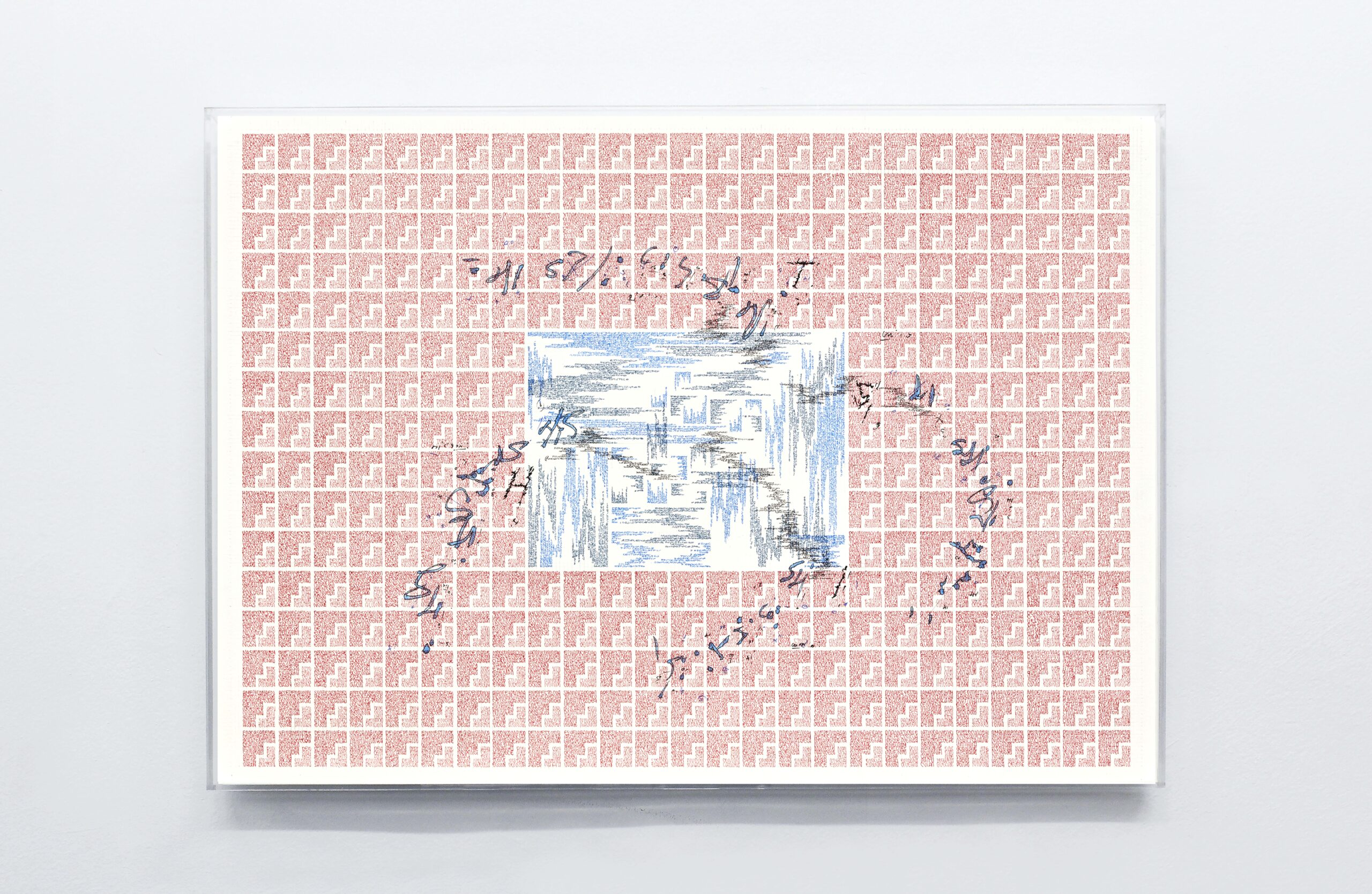

“Un libro sonríe / Una canción se Burla” Transcripción a mano del Libro “Tempestad en Los Andes” de Luis. E Valcárcel y fragmentos de la canción “Las Colinas” de V.A Gil Mallma / “Picaflor de Los Andes”, 2023

125 x 100 cm

Ink on cotton paper

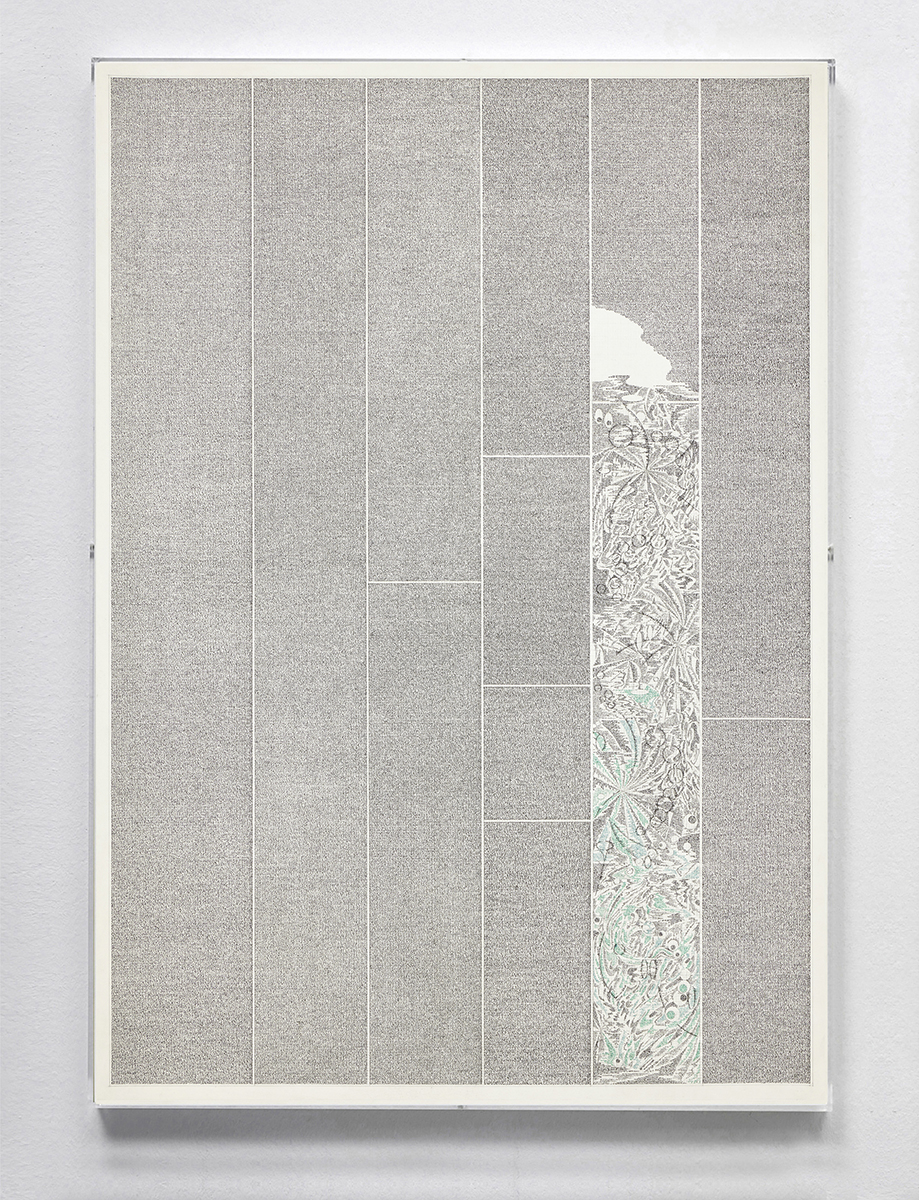

Hand transcription of Edouard Glissant’s book “Poetics of Relation”, 2023

65 x 50 cm

Ink and graphite on bamboo paper

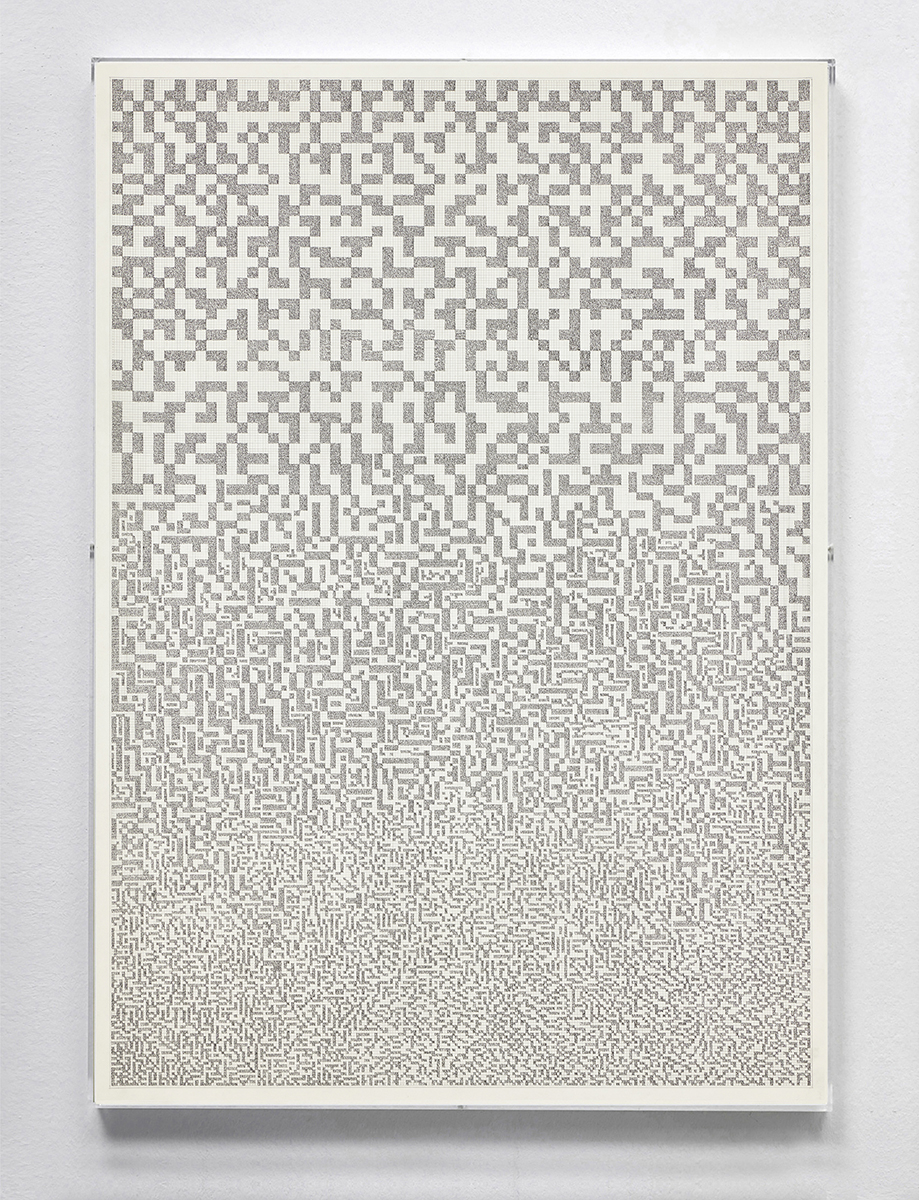

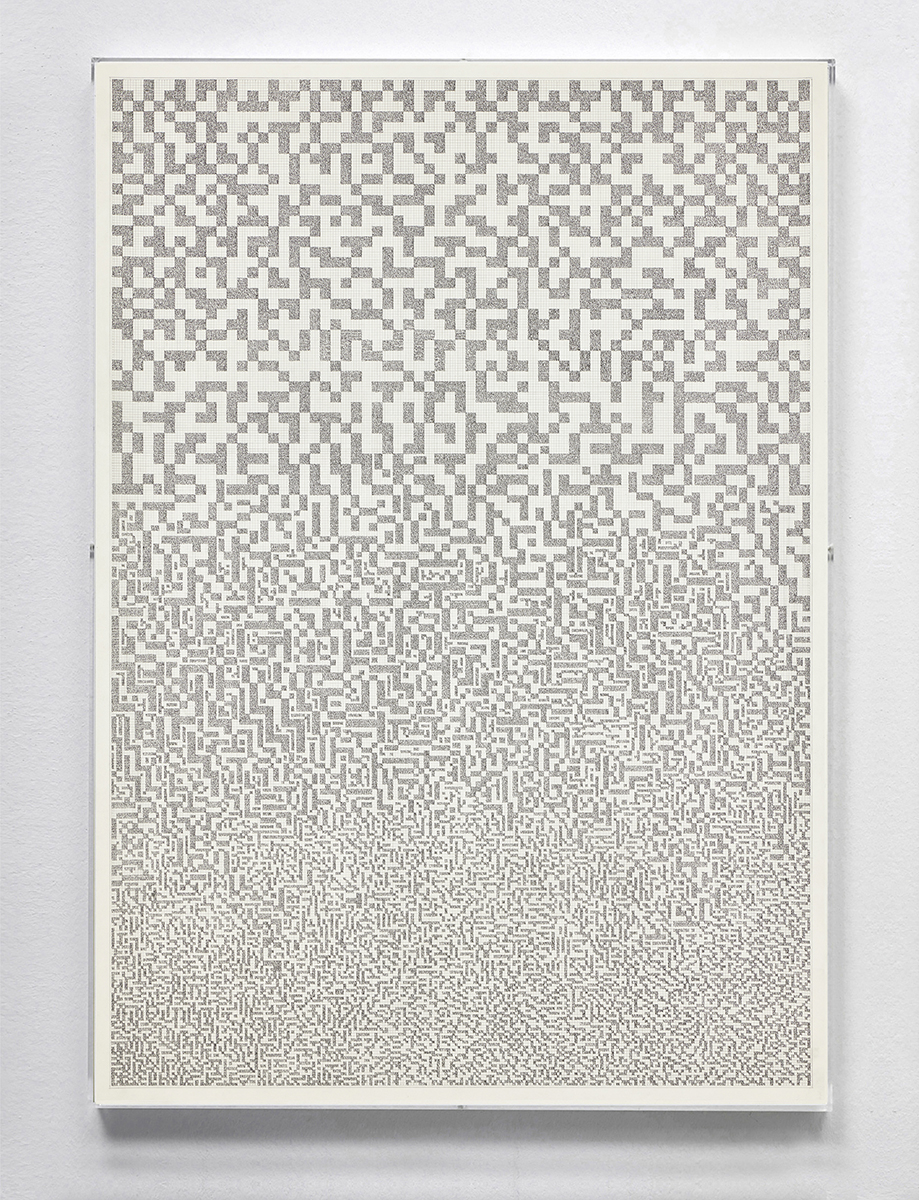

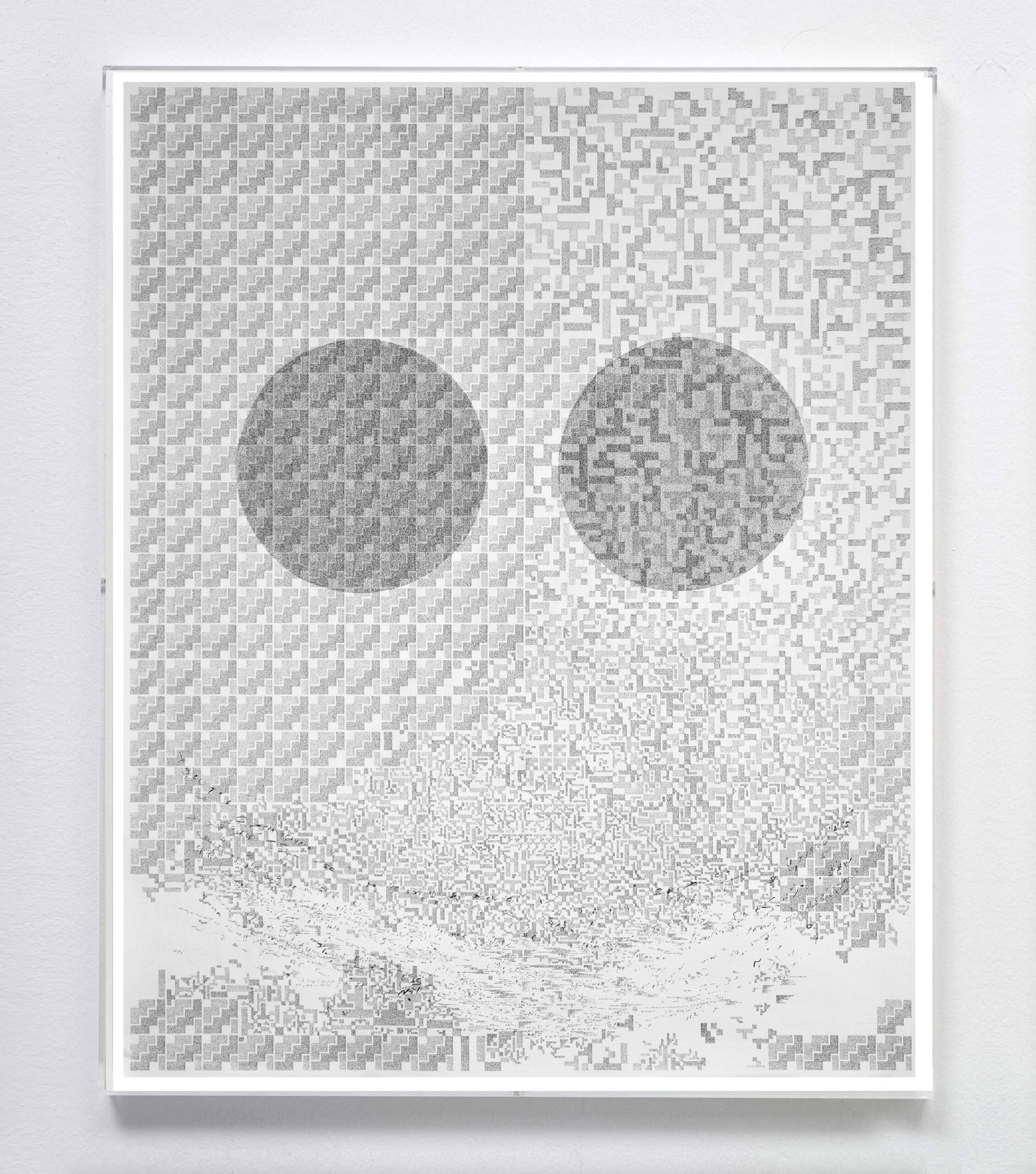

Handwritten transcription of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s book “A thousand Plateaus”, 2022

65 x 50 cm

Stylographs on cotton paper

Handwritten transcription of Edouard Glissant’s book “Poetics of Relation”, 2021

42 x 60 cm

Stylographs on cotton paper